-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Religion: The Price of Being “Different”

People who know me sometimes ask: “How did you get this way?”

What a question.

For the record, I was born the usual way—but beyond that I’ve always been different.

When other kids were playing baseball, I was practicing stand-up comedy. Not a jock. An artist and a writer. Not particularly materialistic. Spiritual. Not reverent. A rebellious iconoclast. While my junior high school classmates marched in blind unison toward a life of middle management and suburbia, I found that Malvina Reynolds’ song “Little Boxes” was a better reflection of my views.

As things turned out, a significant part of my unconventional nature had to do with religion. From an early age I knew I needed to be, wanted to be, and could be a better person and I had a strong notion that improving my spiritual self was going to get me where I needed to go.

In my family, I was alone in that belief. While I was raised in a nominally Catholic household, my parents were agnostic. I wasn’t.

Despite the household agnosticism, I explored Catholic, Protestant and Jewish religious services. I liked the fellowship. A lot. I also liked some of the ideas. But while I got the message loud and clear that I should be a better person (I already knew that) I didn’t find in them a practical way to go about it. I moved on, which wasn’t easy because everyone I knew went to some church or other and all had definite opinions about where I’d end up on Judgment Day. But I did move on—looking over my shoulder, just in case.

The fact is, Scientology is different in some ways from many other religions and not so different in other ways. Either way, so what?

When I was in my early teens, my dad’s business partner gave me a copy of The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran. To this day I have no idea what possessed him to do that—he was even further away from all things spiritual than my parents—but it was like water in the desert. I devoured it in one sitting. Here were ideas without dogma. Here was “how to live” instead of “you’re gonna die.” It was refreshing. It was also a little too flowery and left me thinking: “that’s a good start, but what comes next?” So once again, I moved on.

Then came mid-60s pop psychology and the New Age movement (bleh!) and long-established Eastern religions—which were philosophically closer to what I was looking for, but still not right for me.

At this point I had pretty much run the gamut. But there was one long-lasting benefit in my search: while none of the subjects I explored were working for me, I met many people for whom one of the above philosophies and religions was the answer. Some of these people became good friends of mine and remained so for years. The fact that many of our spiritual and religious viewpoints were very different had no bearing on our friendship.

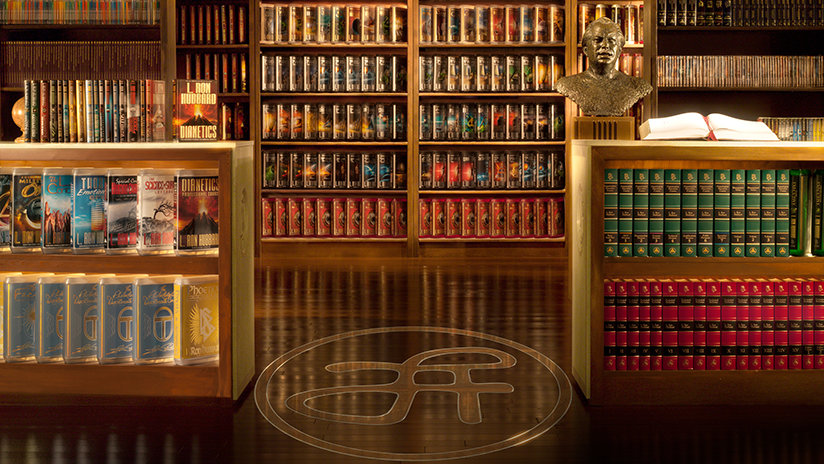

A year or so after college, I discovered Scientology. When I finally got my defenses down and actually took an honest look, I saw something that I didn’t think was possible: here was a philosophy that seemed to match the way I’d been thinking for years. In many ways it was more like encountering an old friend than discovering something entirely new.

That was in 1973 and lo, these many years later, here I am: a member of an “unconventional non-mainstream religion.” I disagree with the label—I generally disagree with any label—but at the same time I jocularly admit that I’m an “unconventional non-mainstream guy.” Hallelujah!

The fact is, Scientology is different in some ways from many other religions and not so different in other ways. Either way, so what? It appears that from the perspective of mainstream American culture, any religion that diverges even slightly from a traditional Judeo-Christian path is unconventional. (Although a number of people would disagree with me about the Judeo part and just stick to the Christian.)

I never had a problem with different religions. When I was a kid—a not-so-Catholic lost soul—my two best friends were Syrian Catholic and Jewish. So? Who cares? In my youthful innocence I could never figure out why anyone would have a problem with somebody else’s religion—but it was obvious to me even then that many people did.

I wish I could reclaim my youthful innocence and scratch my head in wonder when I see “mainstream conventional media” pushing TV programming that attacks “unconventional non-mainstream religion” and religion in general. But I can’t. I’m grown up now. I see this programming for what it is: the irrational urge to attack the unfamiliar that comes from a fear bordering on terror.

What are these people so afraid of? That Jehovah’s Witnesses are personally attacking them by handing them copies of The Watchtower? That a man in a turban is going to change the fabric of the City Council? That Mormons will make them look bad by being too moral? That a Muslim real estate agent is a terrorist? That a Scientologist might poison their minds with The Way to Happiness? The list could go on.

More fundamentally, are they terrified of anything that is even slightly different from what they grew up with? Scared to death of anything outside their comfort zone?

Sure looks that way. And from what I’ve been able to see, while it’s the religions that are being attacked, it’s the individual adherents who end up taking the heat.

And that’s a shame because these Jehovah’s Witnesses, Sikhs, Mormons, Muslims, Scientologists, as well as Hindus, Jews, Buddhists and more are fine people whose only sin is that they’re going about their lives making a living, raising families, involved in their communities and not being a threat to anyone.

At least that’s how I see it.

But remember, I’m pretty unconventional.