-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Scientology: What’s in a Name?

October 1970, Telegraph Avenue, Berkeley, California.

I was a college sophomore. Not only that, I was a college sophomore in Berkeley in 1970—which meant that in addition to being everything that the word “sophomore” implies, I was dripping with attitude: hip, but flower-power innocent—mixed with a cynicism that I wore like a badge. It was an attitude that could only have been engendered in that time and place.

That’s where I first heard the word “Scientology.” I didn’t like the word. Didn’t like the sound of it. What’s this? Science-ology? Isn’t science already an “ology”? And the “T.” What’s that “T” doing there in the middle? Tying the word together, I guess.

It’s amazing how snarky one can get when one doesn’t understand something.

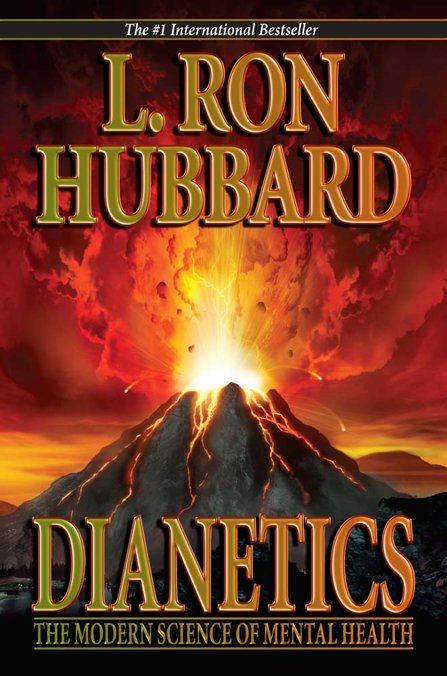

Fast-forward three years. San Jose, California. I was having difficulty in a touchy area of life and a friend who was getting tired of hearing about it read me a passage in Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health that she said she thought might apply. Might apply? It nailed it. Bull’s eye. Despite my cynicism—which was alive and well—I was impressed.

My friend said that a course in communication at the local Scientology Center might help me with the difficulty I was complaining about. Oh, no. That word again. Scientology. I still had issues with that word—but there was also that bit in Dianetics that hit the nail on the head. I bit the bullet and tried the course.

It’s interesting that my first study of Scientology was on the subject of communication, of all things. I knew about communication. I majored in Communication in college. It says so right on my diploma. I recall plodding through a 935-page tome called Modern Theoretical Models of Communication. Each of these models ran about 90 pages. They were intricately constructed and illuminated with loads of elaborate diagrams and each page was rooted in a swamp of footnotes. In spite of this, what impressed me most was the honesty of the authors. Each one said that his model was imperfect and didn’t apply in all cases. Each one declared an earnest hope that more research would be done and that someday a perfect model of communication might be divined.

It was with this background that I entered the Scientology Communication course. The course consisted of a number of drills based on Hubbard’s own model of communication, which he called the Communication Formula. I was curious to see how it worked, but also curious to see if I could find exceptions to it. I figured it should be easy enough to do. The most detailed statement of this formula was only a couple of short paragraphs—almost ridiculously simple compared to my college study. Nothing that simple could work all the time…

I read voraciously. Studied everything I could get my hands on. Tried everything I could. It all worked exactly as stated when applied as stated.

Except that it did. It was humbling. And impressive. After three and a half months of testing it in life, observing others, and comparing it to all I knew of science and the humanities, I could not find a single exception. Not one.

You know, this L. Ron Hubbard guy is really on to something.

I read voraciously. Studied everything I could get my hands on. Tried everything I could. It all worked exactly as stated when applied as stated.

Ah, but that word. It still bugged me a little. I did get the definition: Scio—knowing in the fullest sense of the word; plus logos—study of—equals study of knowing, or study of knowledge, or knowing how to know. Okay, fine, I get it. But still seemed a little, I dunno…

Fast-forward many more years. Two things happened in rapid succession.

The first occurred when I was listening to a recorded lecture. Ron was discussing methods of determining sanity. He described sanity in a number of ways, but the simplest was noting the individual’s ability to compute—think—accurately. The word that got me was “accurately.”

A person who thinks accurately sees a dog, for instance, and it registers as a dog—not as a cat. Not only does he see a dog, but he sees a German Shepherd (not a wolf, which it looks like) and not just any German Shepherd but one who is a year old and whose jumping and barking are not signs of incipient attack but an invitation to play. Thinking accurately is not identification: dog is the same as wolf which is the same as death. Thinking accurately is differentiation: this particular dog is a playful pup.

This seemingly innocuous bit of information could save your life. If you identify this playful pup as dangerous and panic—which is really a misidentification—it could smell your fear and go into the attack mode that is deep in its DNA, which could mean you’re about to have a very bad day. If, on the other hand, you correctly differentiate—this is not a vicious dog, it’s a playful pup—you and the dog are in for some rollicking fun.

Listening to that lecture prompted me to recall that Ron had emphasized this point as early as 1952—only a couple of years after his first book on Dianetics. He said, “differentiation is a condition of the highest level of sanity and individuality.” Further, he put the ability to differentiate at the very top of the scale of survival traits for any individual. I had known this for years but had never fully appreciated it as a rock-bottom fundamental to the entire philosophy. Indeed, one could say that the ability to fully differentiate in all of life’s circumstances and under any amount of stress is a big part of the end goal of Scientology for the individual.

The second thing that happened was my looking more deeply into the history of scio—the basis of the first couple of syllables of that word: Scientology. Dig far enough and you’ll find that scio goes back to an earlier Latin word that meant “to separate one thing from another: discern.” In other words, differentiate. Bingo!

For me, that was the missing ingredient. Putting it all together—scio plus logos—the definition of Scientology could be refined and expanded as the study of how to differentiate and thus be certain of what you know, which gives you a fighting chance at survival when times get tough. The name says it all: “Scientology” is a one-word description of one of its most basic tenets.

Of course it is. Mr. Hubbard had a background in engineering, so naturally he’d come up with an efficient word. Recognizing that, my last bit of reservation turned into admiration. Scientology is the perfect name for this religion and its underlying philosophy. Simple. Elegant. Descriptive. It fits it to a “T.”