-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

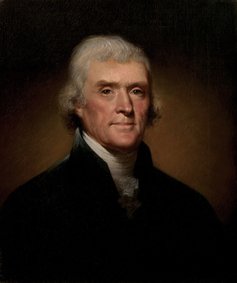

Jefferson, Adams, Religion & Freedom

A while ago I wrote a post about a squabble in Arizona over whether a humanist could give a benediction to the state legislature that didn’t mention God. There were strong feelings on each side. I mentioned Jefferson as having once said that “it does me no injury for my neighbor to say that there are twenty gods or no god.”

I thought of that post recently when I ran across a letter by John Adams on the importance of religion in society. It reminded me that just like today, people of the founding generation were not of one mind on the subject of how religious freedom should be exercised. Adams’ most well-known quote on religion is from a 1776 letter in which he proclaimed that “it is Religion and Morality alone, which can establish the Principles upon which Freedom can securely stand…. The only foundation of a free Constitution, is pure Virtue.” He followed this up a few years later by remarking that: “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

The names of Jefferson and Adams are linked together in American history in part due to the long exchange of correspondence in the last years of their lives which included an open discussion of their often contrasting religious views.

Adams’ outlook on religion contrasted with that of Jefferson’s because Adams was born and bred in the Massachusetts Puritan tradition. Adams was the primary author of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780 which included special privileges for the Congregational Church (into which the Puritan movement had evolved), while Jefferson drafted the Virginia Religious Freedom Bill which attempted to make religion free of any government control. Jefferson also famously advocated a “wall of separation” between church and state.

On the other hand, it’s hard to imagine Adams feeling comfortable with a humanist benediction like the one delivered in Arizona. At the same time, Adams’ life at the forefront of our transformation from a group of colonies to a republic made him reexamine many things. In 1820, for example, he proposed an amendment to the state constitution that provided for complete religious freedom.

Jefferson, the religious radical who edited the Bible down to the few pages he felt comprised the essential teachings of Jesus, might have been more at home in our heterodox times. But if he did show up in the twenty-first century, he might remind us, as he wrote in his own day, that “peace, prosperity, liberty and morals have an intimate connection” and express his hope that by making religion free, people would come to their own understanding of God.

The names of Jefferson and Adams are linked together in American history in part due to the long exchange of correspondence in the last years of their lives which included an open discussion of their often contrasting religious views. To get to the point where they could freely write to each other took some work after being bitter political rivals, with Jefferson defeating Adams in a tumultuous presidential election. But they did it.

And in the volatile and divisive political and social climate of today, their example of what became a lasting, enriching friendship and free exchange of views—between a Puritan Yankee and a Southern-gentleman free-thinker no less—is more than a little bit refreshing. Each in his own way saw religion as a vital element of a free society, but only if it came with the complete freedom of individuals to examine it for themselves.

Two centuries later the example they set becomes ever more relevant. They showed that we have the ability to overcome prejudices and past hostilities, even when these have taken place in the glaring light of national politics. We can do the same.