-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

How it Felt to Be Treated Like a Nazi

When I was in third grade, I had a teacher who despised me.

It wasn’t because of anything I’d done to her, and it wasn’t that I was a difficult student.

In fact, I loved learning, was an avid reader, and was pretty social, so school was a perfect fit.

Except for Mrs. Goldwitch.

That was the nickname we had given her. “We” meaning me and two of my closest friends.

I had two strikes against me in Mrs. G’s eyes: I had a German surname and I was a Scientologist.

Sure, I was hardly 8 years old. But as far as she was concerned, I was just as guilty as the Nazi Germans who had murdered and oppressed her people.

And to this day I have no idea why my being a Scientologist was a problem. Neither of my other two friends was of German descent, but they were both from Scientology families as well. She was mean to each of us—but me especially.

I wish this was conjecture on my part. But it wasn’t. I’ll never forget the moment she gave me an impossible assignment with the hopes of failing me, and when I objected, she narrowed her eyes, leaned down close to my face with raw hatred, and told me that “my kind” didn’t deserve fair.

I remember feeling something I had never felt before: hate.

As a child with a wild and beautiful imagination, and a naive sense of wonder and interest in the world around me, it was such a dark, new feeling that I was certain it would change me forever for the worse.

So this hatred she directed at me, it had stirred a darkness in me that I had never felt before, and it frightened me because it made me want to be cruel right back.

I grew up with the notion that people were simply people and you judged them based on their character—not their color, age or gender. My girlfriends were white, pink, yellow, black, Scientologists, Jewish, Christians, whatever. None of us cared a smidgen as long as there were Legos, bikes and Barbies.

So this hatred she directed at me, it had stirred a darkness in me that I'd never felt before, and it frightened me because it made me want to be cruel right back.

First, I boycotted her class (which basically meant school) for three whole days, but finally had to go back.

My mother could see that I was troubled by this. Not the little-girl sort of troubled, but more like a deep sort of troubled usually reserved for adults with important things on their minds and great difficulties. She pulled me up next to her on the sofa and asked me what was really bothering me about this teacher.

I told her the things Mrs. G would say to me and my friends. The snide remarks about my religion and the comments about my ancestry. And I told her how much it upset me that she hated me and I hated her when I’d never done anything to her in the first place.

She went still for several moments. I can only imagine what was going through her mind, having kids of my own now. But then she did the most remarkable thing. She gave me the gift of compassion, and she gave me a choice.

I sat horrified as she told me the story of the Germans and the Jews. Of the Nazis and the things they had done. I was relieved to hear that I didn’t share a heritage with any real Nazis, but I was ashamed for Germany nonetheless.

There I was, a barely 8-year-old girl, with no grasp of the world beyond Los Angeles, never mind America. And at that moment my hate for Mrs. G dissipated. I felt a sense of understanding and sadness for her and all she must have lost.

And then I buckled down.

I can only imagine what was going through her mind, having kids of my own now. But then she did the most remarkable thing. She gave me the gift of compassion, and she gave me a choice.

One by one, I passed her ridiculously impossible assignments. I treated her with respect and kindness and chose not to lower myself to acting out of vengeance.

Eventually, the quips stopped, and the hatred she felt for me was replaced by a reserved distance, followed by more reasonable assignments and fairer treatment.

I still think of her once in a while. And I can’t imagine how lonely it must be to live in a world where you hate someone for something you don’t understand or for something they distantly represent.

My hope is that Mrs. G found love somewhere along the way, and that other kids won’t feel that sort of darkness in their schools or lives because of their faith or ancestry.

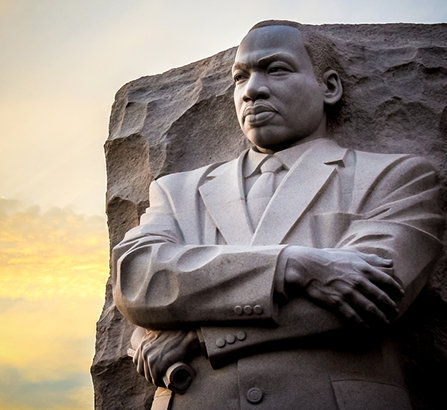

Reminds me of this magnificent quote by Martin Luther King Jr.:

“Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding a deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”

Well said, Reverend King. Well said.

And I leave you with this beautiful passage from the essay What is Greatness written by L. Ron Hubbard in 1966, wherein he addresses the question: When subjected to hatred, what then is the answer to one’s own happiness?

“The real lesson is to learn to love.

“He who would walk scatheless through his days must learn this—never use what is done to one as a basis for hatred. Never desire revenge.

“It requires real strength to love Man. And to love him despite all invitations to do otherwise, all provocations and all reasons why one should not.

“Happiness and strength endure only in the absence of hate. To hate alone is the road to disaster. To love is the road to strength. To love in spite of all is the secret of greatness. And may very well be the greatest secret in this universe.”

Photos by: L. Ron Hubbard Library / Atomazul / Shutterstock.com