Theophobia Part I: Why a Hatred of Religion?

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on theophobia.

Religion has been on an international statistical decline. The religiously unaffiliated, otherwise known as “nones,” are growing significantly. Nones, composed of atheists, agnostics and those who express no preference toward any identifying label of faith, are now the second largest religious group in North America and in most of Europe, accounting for nearly a quarter of the population in America (per Pew Research) overtaking, in the past decade, Catholics, mainline Protestants, and all followers of non-Christian faiths in the U.S.

Dissatisfaction and disillusionment with “organized religion,” dismay at horrific acts committed in the name of “religion” and the perception that traditional religion has become irrelevant in a modern scientific world have all been put forth as reasons for religion’s current decline. In this, the third in a series on hatred and bigotry, we’ll look at another reason—a calculated and carefully planned attack on religion itself, with roots going back 200 years; an effective and devastating assault through subversion, infiltration and propaganda, born of an actual hatred of religion itself: theophobia.

Among religion’s many great gifts to the world are community, purpose, and the dream of aspiring to something higher than oneself.

Religion’s beginning, much like many creation stories, is not precisely dated, and comes from a past so distant that religion becomes as timeless as the questions it poses: Who are we? Where did we come from? Where are we going? Why?

Although other species of animals and plants possess varying degrees of intelligence, can communicate and can experience emotions such as love, grief and anger, none to date have been known to formulate anything like a set of beliefs and practices through which they may struggle with the ultimate problems of life—evil, pain, bewilderment and injustice—and which provides some hope of relief from those problems. This definition of religion, as outlined by J. Milton Younger in his A Scientific Study of Religion, only applies to human beings, and may be what truly distinguishes us from other life forms on this planet in the end.

But religion does more than ask questions and ponder answers. Among religion’s many great gifts to the world are community, purpose, and the dream of aspiring to something higher than oneself. And the net effect of religion, as L. Ron Hubbard wrote in 1951, is that: “No culture in the history of the world, save the thoroughly depraved and expiring ones, has failed to affirm the existence of a Supreme Being. It is an empirical observation that men without a strong and lasting faith in a Supreme Being are less capable, less ethical and less valuable to themselves and society… A man without an abiding faith is, by observation alone, more of a thing than a man.”

As to what happens to a culture without faith, Mr. Hubbard continues, “Materialistic science operating on the premise that Man came from mud only, that the mind is a queerly erroneous stimulus-response mechanism, that the human soul is a delusion, that God was a myth of some aberrated Mesopotamian, has presented us at last with the immediate and real threat of Man’s extinction as a species.”

There have always been those who distrust believers and practitioners of faith and religion. Often that distrust has targeted specific religions or religion in general, and often that distrust has mushroomed into intolerance, repression and bloodshed. One could arguably say that if religion came into being untold ages ago, that hatred of religion is its only slightly younger relation.

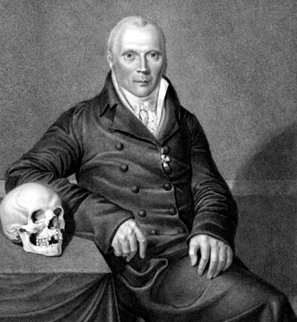

But unlike the “birth” of religion, the modern hatred and assault on religion can be precisely dated: 1879, Leipzig, Germany. In order to fully understand theophobia, however, we must go 71 years prior, to 1808. That was the year that German physician and physiologist Johann Christian Reil coined the word, “psychiatry,” to describe the emerging study of the treatment of the insane. Reil felt that mental patients needed treatment of a moral, theological means, with a medical hand nearby to handle any physical aspect of the patient’s distress. Hence, the new name for the subject, which literally means “a doctoring of the soul,” from the Latinized Greek psyche meaning “soul,” and iatreia meaning “doctoring care.”

Reil’s “moral, theological” approach at first met opposition by those in the mental health profession. But as the 19th century wore on, many realized they could pretend to embrace that philosophy while arguing that, since mentally ill people were often suffering physically, a purely physical approach was also vital. Rapidly over the decades, the physical aspect of psychiatry gained sway over the mental-spiritual side (being more profitable) until the clergyman and philosopher were made irrelevant in handling the mentally afflicted, and the field became fully the domain of the “professional” biologically-oriented psychiatrist.

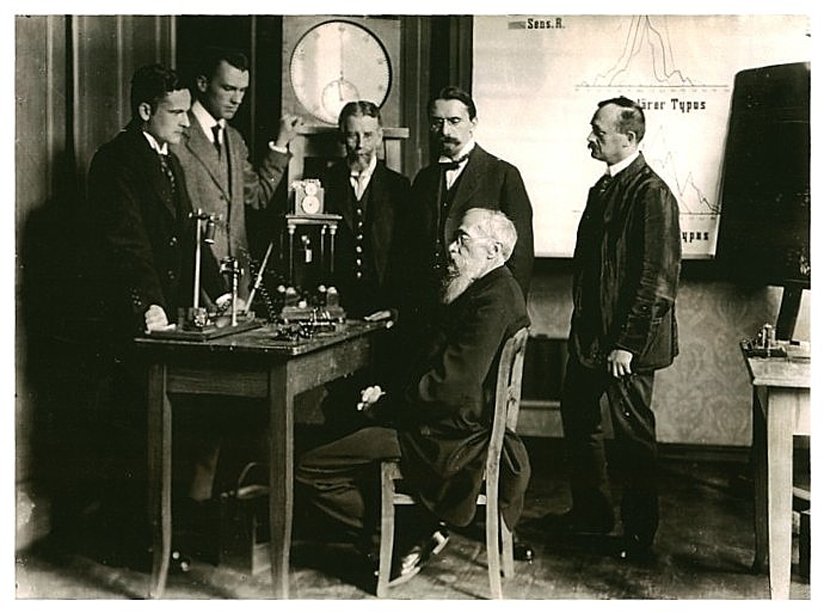

The transformation from psyche to nullum-psyche, or “soul” to “no soul,” was completed in 1879 by Professor Wilhelm Wundt, who declared to his students at the University of Leipzig that the soul was “a waste of energy,” that man was simply another animal who could be conditioned to different ideas about the value of human life. Religion, he said, “was a kind of primitive metaphysics.” The concepts of soul, spirit, religious ideas, faith and feelings were now all “scientifically” relegated to primitive races.

With that, the gauntlet had been hurled down. Religion was not only useless and meaningless, it was an impediment—a conditioned reflex of the brain that could and should be treated. The door was flung wide. The 20th century brought open season on all things religious, including its most sacred trappings and figures. Religion was no longer religion, according to Sigmund Freud, but “universal obsessional neurosis.” In 1910, Charles Binet-Sangle published The Madness of Jesus, which concluded that, “the nature of the hallucinations of Jesus as they are described in the orthodox Gospels, permits us to conclude that the founder of the Christian religion was afflicted with religious paranoia.”

Religion had little defense against the attacks. By its nature, as a thing not stemming from logic but from faith, religion was easily gutted by the pitchforks of its “logical,” “scientific,” “modern” psychiatric critics.

“We have made a useful attack upon a number of professions. The two easiest of them naturally are the teaching profession and the church.”

St. Thomas Aquinas had written six centuries earlier: “To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”

No explanation is or was necessary for the faithful. Those whose belief in religion is steadfast need no diagnosis of their spirit, no dissection of their conviction, no surgical incision in their souls to see what is inside. But their ranks were beginning to thin as psychiatry’s star rose during the era of the World Wars and in their wake.

In 1933, psychologist John Dewey wrote, “There is great danger of a final, and we believe fatal, identification of the word religion with doctrines and methods which have lost their significance and which are powerless to solve the problem of human living in the Twentieth Century.”

With the advent of World War II, whatever pretense remained that psychiatry and religion were not enemies was shed on both sides of the conflict. German psychiatrists eagerly got in on the ground floor of the Holocaust, devising efficient systems of identifying, transporting and slaughtering hundreds of thousands of “mentally ill” and “racially and cognitively compromised individuals,” even accommodatingly providing six psychiatric institutions for the purpose of gassing their victims (the institutions were Brandenburg, Grafeneck, Hartheim, Sonnenstein, Bernburg and Hadamar). German psychiatrists were central and vital to the effectiveness of Hitler’s Final Solution, putting their theories and organizational skills to full fruition. One psychiatrist, Dr. Imfried Eberl, even ran a death camp, Treblinka, until he was fired for inefficiency in the disposing of corpses..

Meanwhile, on the other side of the global conflict, the assault took a subtler turn. In 1940, British psychiatrist John Rawlings Rees laid out his Strategic Plan (literally an outline for the conduct of a war) for mental health, wherein he detailed his plan for psychiatry’s takeover of the fields of education, law, medicine and the church: “Public life, politics and industry should all of them be within our sphere of influence... We have made a useful attack upon a number of professions. The two easiest of them naturally are the teaching profession and the church.”

His colleague, Canadian psychiatrist G. Brock Chisholm, seconded Rees’ point in a speech in 1945 calling for the eradication of traditional concepts of right and wrong, asserting that “psychiatry must now decide what is to be the immediate future of the human race. No one else can.”

Three years later, Chisholm and Rees founded the World Federation of Mental Health (WFMH) with themselves as co-chairs. At its inaugural conference, the members of the WFMH targeted religion as its first victim, agreeing that psychiatry “carries an obligation to examine critically some of the teachings of the church in light of present-day insight…”

In response to which one attendee, psychiatrist Henry Stack Sullivan, commented that his profession, like all great “religious leaders, prophets and even Jesus Christ,” should bring religion “up to date.”

And, with the same relish as their Nazi counterparts, they did just that. Within months, deals were struck with Christian denominations in the UK and U.S., allowing psychiatrists advisory, referral and commitment powers. The Methodist Church aligned itself with psychiatrist Percy Backus and established psychiatric clinics as an extension of Christian pastoral counseling, and aggressively promoted “deep sleep therapy” (prolonged narcosis) electroshock and psychosurgery as essential supplements to Christianity.

“The word ‘soul,’ has lost its meaning and even its plausibility,” said clinical psychologist Paul Pruyser.

By 1952, 83 percent of more than 100 U.S. seminaries and graduate theological schools surveyed had one or more courses on psychology. By 1961, around 9,000 clergymen had studied psychology-based “clinical pastoral” counseling courses.

And what was taught in these courses? Responsibility? Right and wrong? Moral values? Mmmm... no. Those things were simply “unscientific.”

Clinical psychiatrist Canon Sydney Evans, 1967: “What does personal responsibility mean in… the light of the findings in psychoanalysis? Do the words right and wrong have any further meaning in the light of our new knowledge of compulsive behavior patterns… I believe it’s one of the tragedies of Christianity that it has got itself all mixed up in morality.”

Psychiatry’s swindle worked so well on the clergy that, in a very real sense, it became a new secular church within the church, with young aspirants educated in psychological techniques, methodology and theory, often taking precedence over or superseding theology altogether.

“The word ‘soul,’ has lost its meaning and even its plausibility,” said clinical psychologist Paul Pruyser. The clergyman “will find that whether he wants it or not, he is also a front line mental health worker.”

Psychiatry and its sister subjects, psychology and psychoanalysis, made their presence felt in the decades following the formation of the World Federation of Mental Health by infiltrating, diluting and ultimately poisoning the teachings of religion. Morals, family cohesion and church attendance all declined as grants to psychiatry—along with statistics of crime, violence and drug use—skyrocketed.

In 1964, one such federal grant (from the National Institute of Mental Health) funded a three-year experiment on two dozen Catholic religious orders. The “study” ended after two years, with 300 of 560 nuns at one convent petitioning Rome to get out of their vows within the first year. Decades later, one of the two psychiatrists involved admitted to “corrupting a whole raft of religious orders in the 1960s,” and that what was labeled “sex education” was actually “sexual experience.”

Psychiatry has never let lack of results or disastrous effects on society get in its way.

The psychiatrist in question, William Coulson, further admitted that the psychological techniques used on clergy were aimed at “provok[ing] an epidemic of sexual misconduct among clergy and therapists.”

A 1993 Orientation for the Celibate Way of Life seminar for young candidate priests in Germany included the following in its questionnaire: “I consider it a prerequisite for real sexual pleasure if ______,” “the most exciting sexual experience where I felt especially physically and emotionally happy was ______,” and “at the moment I am able to handle my need for tenderness and eroticism to the following extent ______.”

“Exercises” at the seminar included pairing the young candidates off with a cushion at pelvis height and pushing against each others’ genitals with it.

The Swiss Catholic Weekly reported in 1994 that, rather than “an orientation to celibate life,” it was “a seduction of future priests” aimed more at “arousing the desire for sex.”

Considering the Church’s current headache involving the epidemic of pedophile priests dating back to the sixties, it’s difficult not to draw a connection between what’s happening now and what began decades ago when young priests and nuns were used as sexual guinea pigs under the guise of “science” by a “healing” profession that itself has the highest rate of abuse of minor patients. (At least 10 percent of the 650,000 psychiatrists and psychologists worldwide admit to sexually abusing patients. Psychiatrists and psychologists also have the highest drug, divorce and suicide rate amongst physicians.)

Coulson himself summed it up best, confessing that what he and others had done was “really evil.”

By 1994, the circle was complete. Religious faith was now officially a category of mental disorder, induced delusional disorder, enshrined in The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, page 104, published by the World Health Organization—one of psychiatry’s meal-ticket manuals for insurance money gained through the creation of ever-increasing numbers of mental disturbances, disorders and illnesses.

Psychiatry has never let lack of results or disastrous effects on society get in its way, and it wasn’t about to let the moral and spiritual teachings of prophets derail its own zeal for profits.

Religion trusted Science, and, being Religion, accepted the proffered hand of psychiatry.