The Origins of Our First Amendment—the Province of Religion Versus the State

In the United States today we think of the right to religious freedom as a right protected by the First Amendment to our Constitution—a personal right, a guarantee against a certain type of government action affecting an individual.

But it is also more than that; it is a right of religious institutions.

The UN Declaration of Human Rights Article 18 makes this clear, explicitly stating that persons may exercise their religious liberty “in community,” while the U.S. Constitution reads: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

The United States Supreme Court has consistently held that religious freedom is a right for an individual as well as for an institution composed of individual persons. The right of religious freedom is capacious. It can be exercised by a person who is acting personally, apart from any religious institution, or it can be exercised by the institution in its official functions.

The right of religious freedom is capacious.

In fact, religious freedom is so capacious individuals can claim religious freedom even when the religious institution they are part of might not insist on a behavior the individual asserts is compelled by their religion. For instance, in a 2015 Supreme Court case, Holt v. Hobbes, a convert to Islam, who was incarcerated in the prison system, claimed his faith compelled him to wear a beard. The wearing of beards was prohibited by prison regulations, and officials cited security reasons for the rule and applied it without exception. They reasoned that contraband could be hidden in a large beard or that the growing of a beard could disguise the wearer in a way that would make prison security more difficult to enforce. Holt said as a Muslim he had to wear a beard, even though Islam does not require men to wear beards. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court sided with Holt claiming that his religious freedom had not been properly accommodated by the prison and that some way could be found that allowed Holt to keep a beard without jeopardizing security.

The Supreme Court has also held consistently that religious institutions have a right to be free from government interference when it comes to the setting of their own rules and doctrines. In a case involving the Serbian Orthodox Church Diocese for the United States, the Court declined to get involved in a dispute over how the individual parishes should be organized into dioceses according to church rules. The justices deferred to the institutional authorities of the church, even though the dispute implicated the property of U.S. citizens who were members of the warring parishes. (Serbian Orthodox Church Diocese for the United States v. Milivojevitch, 1976)

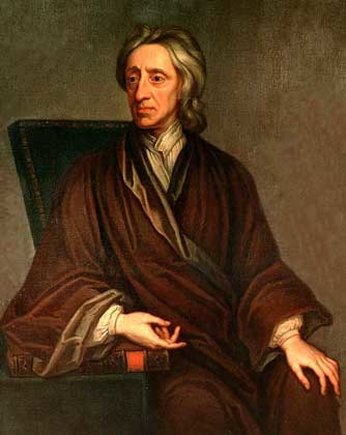

This freedom from government interference on the part of institutional religious organizations is based on an insight that John Locke expressed in his famous 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration. Locke, a 17th-century English philosopher, had such a profound impact on the American system that he has been called an honorary American founder.

Locke was known for his moderation, but he had clear sympathies with parliamentarians who were trying to find legitimate limits on the sovereign power of the English king. His letter realizes that the church has certain powers that are outside the ambit of the state, because the church is an institution that in many cases, certainly in the case of England, long predated the reign of any line of English sovereigns. So the church did not require the permission of the state to function. Rather, it had a legitimate sphere of action that the state could not rightly invade.

Part of that sphere was the determination of what constituted church doctrine. The king was simply “incompetent” to rule on such matters. It was the church itself that knew what its history was, what its traditions were, and what its teachings were. As long as a religious institution otherwise abided by civil laws keeping the peace, and tolerated other religions, the state was incompetent in matters of religious doctrine.

The king was simply “incompetent” to rule on such matters. It was the church itself that knew what its history was, what its traditions were, and what its teachings were.

The king, for instance, could not say the Church of England was right when it came to its theology of the Eucharist and the Methodist Church was wrong, even though in England the king was the head of the Anglican Church. Locke suggested something different in limiting the power of the king over religious faith.

The American founders adopted this understanding in their decision not to establish a state church in the newly formed country. They believed that religion is a matter of free choice for individual citizens, following Locke’s suggestion that the choice of a religion should be voluntary. Because the state is incompetent in matters of faith and doctrine, it cannot require that a religious group believes a certain thing or holds to a certain religious form of government.

This would extend not just to matters of theological doctrine but to matters of polity and discipline as well. As we see in the Serbian Orthodox case, this would extend to matters of church organization, but also beyond. So if the Roman Catholic Church, for example, says that the seal of the confessional is sacred and may not be broken even when a penitent confesses a felony to a priest, the state cannot supersede that rule with a mandatory reporting statute that requires crimes to be reported to the authorities when heard by priests. It would also apply to statements made by Scientologists to their ministers in the process of Scientology spiritual counseling. The state cannot reinterpret those actions as something else.

In the case of Christians, for example, the state cannot say that telling someone else some bad thing is no different whether it is done in the process of the sacrament of penance or while talking to a teacher in a public school. Nor could the state say Catholics are letting minors drink wine in violation of the alcohol beverage laws and that it matters not that the church calls it drinking the blood of Christ.

As difficult as some of these cases may be, courts have usually sided with the church and with the Lockean ideas. The church, not the state, distinguishes between human actions based on their religious motivation or lack thereof.

Of course, every action is simply a human action even if it is done by a pious person. Many religious rituals are essentially simple—actions like eating bread and drinking wine, washing with water, telling someone what is bothering you, singing, or helping people less fortunate. Religious institutions, not some state regulator, get to say what those actions mean. Otherwise religion is just another activity controlled by a minority that holds power and loses its ability to exist separate from the state.

Why is it important to insist on both the personal and institutional aspects of religious freedom? Because if it is reduced to simply a personal right, it could be interpreted to mean something like a right to conscience or free thought. It is not simply that. We do not really need to have a legally protected right to conscience; governments cannot force people to think a certain way. In fact, they cannot even know what citizens are thinking unless they express those thoughts in words or action. Language and action are social at their core, as is religion—which is more than private belief, more than “spirituality.”