-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Religion in Schools: Does it Work?

People who know me often raise at least one eyebrow when I tell them that the bulk of my high-school education occurred in a Convent Catholic school. It was not always a walk in the park academically but at least it gave me the discipline and necessity to come out the other end with a few diplomas to my name! I actually did pretty well with it. But when it came to the subjects of sex ed and religious studies, the curriculum might have been described as “somewhat questionable.”

The former was restricted, to say the least, administered solely by a nun and a priest, the latter followed a purely Catholic bent. So much so that, while growing up, I was pretty oblivious to any faiths or denominations besides Catholicism and the Church of England (I grew up in the UK). It was only around the age of 15 that I came across a Hare Krishna and discovered that other creeds (besides Judaism, which I had vaguely heard about) were extant in the world out there.

Many years later, one weekday afternoon, I came to pick my six-year-old daughter up from school—an establishment in a small village in northern France. Her teacher was outraged: one of her colleagues had had the “gall” and “stupidity” to create a nativity scene in her classroom for Christmas! Faced with my incomprehension over her complaints, she explained to me the “gravity” of the situation: (as in many countries worldwide) all French state schools are secular by law, which means religious studies of any nature are forbidden under all circumstances.

“Religious studies” should, in my view, be just that—a comparative study of a whole array of religions, giving an overview of spirituality in the world.

This jarred me somewhat—not only because she was so forceful about her protest but also because, despite my sketchy and slanted religious education in my youth, at least the concept of religion itself had been embraced within my school’s curriculum. Surely some kind of spiritual reference is better than a complete denial on the subject…? To corroborate this, according to the Pew Research Center, an article published in December 2012 regarding religion and public life states that “worldwide, more than eight-in-ten people identify with a religious group.” Excluding spirituality from everyday life is surely not a valid proposition. Okay, so schools and religions are not necessarily joined at the hip but in a traditionally Catholic country like France, a nativity scene at Christmas doesn’t seem too out of place…

A group in New Zealand named Secular Education Network (SEN) shares the same viewpoint as my daughter’s former teacher. According to this article, SEN’s members have been handing fliers to parents outside schools in a campaign against religious instruction in public education. They’re concerned about the content of these lessons, claiming it is purely Christian-oriented. A religious instruction provider for 600 schools in New Zealand, however, argues that “the material is old and the group is misinformed.”

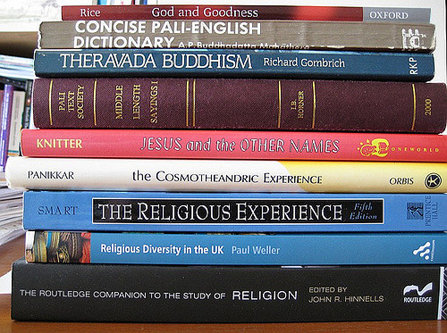

I think I see where the problem lies here, at least from my standpoint: I would personally object to having my children educated in a way that I saw as restrictive or even bigoted. “Religious studies” should, in my view, be just that—a comparative study of a whole array of religions, giving an overview of spirituality in the world. According to David Barrett et al, editors of “World Christian Encyclopedia: A Comparative Survey of Churches and Religions—AD 30 to 2200,” there are 19 major world religions which are subdivided into a total of 270 large religious groups, and many smaller ones. Yes, Christianity is generally agreed upon as the world’s largest religion, but what of the remaining 18 or more officially recognized faiths?

In my opinion, the members of New Zealand’s Secular Education Network should be pushing for comprehensive religious education in schools instead of striving to abolish it wholesale. Unless they are simply downright intent on denying spirituality to the natives of the “Land of the Long White Cloud…”[1]

[1] English translation of Maori name Aotearoa, i.e. New Zealand