-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

My Father’s Journey from Darkness to Love

My father was raised an Orthodox Jew in the early part of the last century, in the same Southwest Washington, D.C., neighborhood that nurtured young Al Jolson. As an Orthodox Jew the most important thing in life was to study the Torah and the wisdom of the rabbis of old, as collected in the Talmud.

After a day in public school, my Dad and other Jewish boys would gather in a small, dimly lit chader (literally “room” in Yiddish). There in the semi-darkness he pored, line by line, through the enormous volumes of yellowing, dog-eared pages of Aramaic and Hebrew, in printing so small that one had to squint to see it in that perpetual twilight.

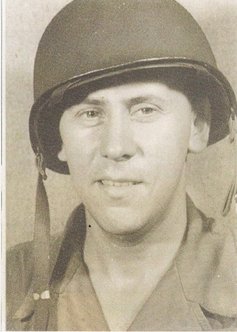

Years later, he served as an officer during the Battle of the Bulge. Following that battle, his outfit fell upon a concentration camp, recently abandoned by the Nazis. A lowering sky exposed thousands of rotting corpses. A few dazed survivors stared, hollow-eyed, at their liberators. My father had been no stranger to bigotry. He was well accustomed to the occasional catcalls, scrapes and bruises gifted him by fools. But this was different. This was government-sponsored hate. Slick. Efficient. Effective. He visited the local mayor and town council and informed them that a truck would come by for them Sunday morning. He expected them to personally bury all the bodies.

“Why us?” the city fathers cried. “We didn’t know what was going on over there! No one told us!”

“You mean no one asked you,” my father answered. “But you knew.”

That Sunday, a dark and rainy morning, my father brought the truck to the town hall and was met by the mayor and his council, all dressed in their finery, their gold chains of office round their necks. Possibly they thought they’d impress him with how grand they were. My father shrugged and said, “If that's what you're going to wear to work, so be it. Get in the truck.” They were given shovels and spent the next several days burying the bodies of people who had done nothing to them but breathe the same air.

Less than thirty years later my father, now president of one of the largest Orthodox Jewish congregations on the East Coast, struggled to understand what had gotten into his renegade youngest son, who had made such outstanding grades in Talmudic study that at one time there had been talk of the rabbinate. I had instead joined a new religion, Scientology. I had done a few courses and liked what I had learned, enough to commit to becoming a professional, and I announced as much to him.

“…thanks to Scientology, the spiritual side of me has awakened, and I now understand not just the words, but also the music of what it is to be a Jew.”

“But it’s a Church,” my father said. “They have a cross. You’re Jewish.”

“And I always will be,” I answered. “But thanks to Scientology, the spiritual side of me has awakened, and I now understand not just the words, but also the music of what it is to be a Jew.”

Over the next few decades I felt my father watch me carefully, making sure I was OK. I had, after all, joined a minority religion. He, too, was a member of a minority religion and was accustomed to the occasional double-takes of strangers. But Scientology, as well as being a minority, was also new, and like all new things, was the subject of suspicion with some. Comes with the territory, as they say.

At length, he raised his hand, like a child asking permission to speak. He said, “I just felt the room fill with love.” He was smiling broadly.

I had become a professional Scientologist, effectively helping many others, but most importantly in my father’s eyes, my wife and I had raised a strong and close-knit family. “Your kids,” he remarked to me once, while observing our three young ones, ages five to ten. “I’ve never seen such integrity in children.”

Toward the end of his life, at the gentle urging of my wife, he agreed to let me give him a spiritual counseling session using my training as a Scientology minister. The love of his life, my Mom, had recently passed away, leaving him adrift and bewildered. I took him in session and for a brief hour we were no longer father and son, but two people creating a space for ourselves safe from the senseless world and free from its ravages of time and loss.

At length, he raised his hand, like a child asking permission to speak. He said, “I just felt the room fill with love.” He was smiling broadly, and I realized in that moment, and perhaps he did, too, that the opposite of darkness is not light, but love.