What’s It Like To Have a Scientologist Parent? According To My 12-Year-Old, “Absolutely Amazing”

Being a mom is my very favorite job.

Full disclosure: I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a mom. I love my work and didn’t know if I could balance work and parenthood. I wasn’t entirely sure if I would be “maternal” enough.

But then my little surprise came along and changed everything. She was the greatest thing that ever could have interrupted my life plan. Two and a half years later, the sweetest boy I’ve ever met joined our family. I call him my “son-shine” because he is a bright light in this world.

Like many men and women, becoming parents changed us. My husband, who is an only child, had never so much as changed a diaper. One day he looked at our daughter, then about 2 weeks old, his expression first perplexed, then astounded, “She’s a little person, she’s not like a puppy or a doll.”

Yep, an actual human being joined our lives.

I came to realize that all of my jobs—as a community leader, as a writer, as an artist—can be done by other people, but I’m the only mom these two little humans have.

Turns out it’s my absolute favorite thing to be.

Raising Little Humans

On Scientology.org, the answer to the question, “What does Scientology say about the raising of children?” reads, “In Scientology, children are recognized as spiritual beings, occupying young bodies. This does not make them any less a person and they should be given all the love and respect granted adults.”

This doesn’t mean that Scientologists see children as “tiny adults,” as in “identical to adults.” What it means is that we don’t treat them as less, just like it says.

My own children took to this concept just about as soon as they could speak for themselves.

I remember overhearing a conversation my son had with his director, at age 4, when my children were in a community theater production of Miracle on 34th Street. It went like this:

“Excuse me, director?”

“It’s okay to call me ‘Debbie.’”

“Okay, Director Debbie, I have a question please.”

Suppressing a smile and and meeting his gaze with a level of seriousness to match his, she replied “Sure, what is it?”

“Why do people keep saying, ‘Oh he’s so cute’? Why don’t they say, ‘He’s such a good actor’?” He continued to look right at her. The question had clearly been weighing on him.

“I don’t know,” she answered honestly, “Maybe it’s something we can work on.”

Director Debbie had her own children, so clearly knew a thing or two about kids resenting condescension, so she spread the word. Soon enough, my son was hearing from fellow castmates, “You’re such a good actor!” He beamed with pride.

Pictures from the play confirm the obvious fact that he was really stinking cute, but at the same time we respected his sense of self. He didn’t want to be “cute.” He wanted to do a good job at the job that had been handed to him.

He was cast in a role which he understood was fake. Each night, for 11 performances, he had to sit on Santa’s lap and, inaudibly (it was background), tell him what he wanted for Christmas. He said things like, “A fire truck, a real one. But I’ll need a fireman too because I can’t drive.” Or “A police car, but a K-9 unit with the real policeman and his dog.” Backstage the actor playing Santa asked him, “Do you really want those things for Christmas?” My son-shine replied, “Of course not, it’s acting!”

My son is like that about everything. He makes sure he can understand his job, and then he does his absolute best at it.

He has responsibilities like cleaning his room, doing the dishes, caring for his hamster and his dog. He works independently. He asks questions of me or his dad—a skateboarding, guitar-playing, snowboarding, mountain-bike-riding adventurer and engineer.

We give him real answers, in terms he can understand. And he does his jobs.

Raising Children with Scientology

Sometimes my children articulate the subjective experience of their upbringing better than we as adults could.

So I sat down with my daughter to ask her a few questions.

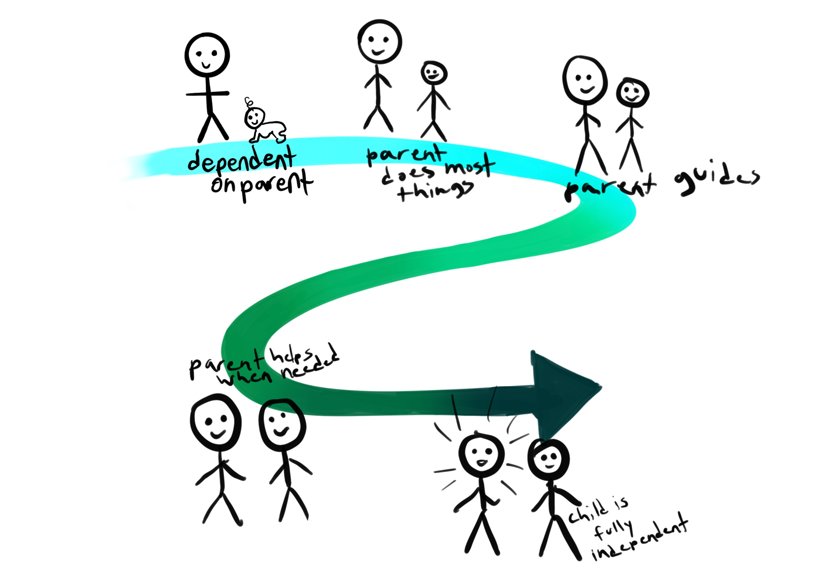

In light of our conversation about increasing independence and preparation for adulthood, she created an illustration on her iPad. It’s a visualization of something she and I have spoken about many times: the road to independence.

Since toddlerhood she has wanted to do things for herself. If she had been a TV character, “No, me do it,” would have been her catchphrase.

But sometimes she still needs my demonstration, my guidance, or at the very least, my inspection of the final product to ensure a job well done. Her illustration applies to everything from cleaning her room to doing her homework and managing her own money—there are stages, levels of my involvement, to assist her in becoming an adult.

Let’s call her Jasmine (her chosen pen name for this article). I asked her these questions and quote her directly. I didn’t let her know in advance what I would ask, because I wanted her candid replies.

Me: “Jasmine, what can you tell me about what your growing up is like?”

Jasmine: “It’s an adventure. It’s fun. Our family is very crazy in the best possible way.”

Me: “What do you think your parents do well?”

Jasmine: “I think telling me ‘no’ once in awhile, letting me and [my brother] sort things out for ourselves sometimes, but knowing when to step in.”

(Side note: I was one surprised mother to hear her say telling her “no” is a good thing!)

“Be less wasteful with trash and stuff. And make sure that the next generation is educated so we are ready to be the adults.”

Me: “What could we do better?”

Jasmine: “Um…” very long pause, “just give me space sometimes. I mean, like, when I’m trying to do something by myself other people come and are like ‘I’ll do that with you,’ you know? Or when I’m already doing something and then Daddy comes up and tells me about some random thing he might do in the future.”

(This is a girl who likes her “me time.”)

Me: “What is it like being raised with Scientologist parents?”

Jasmine: “Absolutely amazing. You have the technology to know how to raise us right and you know all the things you need to know, but you’re still making decisions for yourself, and since sometimes LRH uses big words [my brother] isn’t able to do the courses, but I am and I really like them and I’m so glad I’m in a family that has that technology for me.

Me: “Would you call yourself a Scientologist?”

Jasmine: “Yes.”

Me: “Why do you say that?”

Jasmine: “Because I’ve done a lot of courses* and I believe what I read there is true and I want to do lots more courses.”

Me: “Do your friends and peers at school know anything about Scientology? If so, what?”

Jasmine: “My teachers know more about Scientology than my peers. I don’t really talk to my peers that much about it. I do tell my teachers about it and a couple of my teachers have done courses because of that.”

Me: “What do you think adults could do to make the world better for you and your peers to be the adults someday?”

Jasmine: “Be less wasteful with trash and stuff. And make sure that the next generation is educated so we are ready to be the adults.”

*Some of the courses Jasmine has done can be found online at scientology.org. A couple of her favorites are “Integrity and Honesty,” “Targets and Goals” and “Communication.” She read at 7th-grade level at 10 years old, when she first decided she wanted to study Scientology.

Real Talk

Being a parent can be a challenge. Our own weaknesses sometimes glare in our faces, blinding us from the best course of action.

But the biggest thing my husband and I have gotten out of being parents has been to improve our own communication, because communication is the fabric of living—the threads we use to coordinate, express and share affection for one another—but also the way we get ourselves into knots and upsets. There’s a real technology to good communication, to untying the upsets that occur and getting things woven right again. Scientology has helped us with that.

We speak to our kids like real people. If we mess up, we own up and try to do better.

We make decisions about chores and screen time. We sort out upsets between them or their friends. We help with homework or praise their accomplishments. Sometimes it’s a job with long hours, but getting paid in snuggles is incredibly rewarding.

All in all, it’s a great gig.

And it seems like the kids think we’re pretty amazing at it.