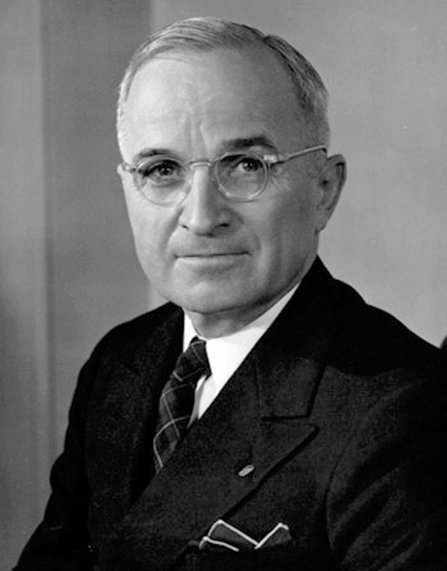

Taking Action Against Discrimination: Harry S. Truman

The first of a “Taking Action Against Discrimination” series.

He could not possibly win. Almost everybody said so. His two opponents for the Democratic senatorial nomination were better financed, better looking, and better supported by the party machine. But Harry S. Truman persisted. He drove himself around Missouri, sleeping in his car when his campaign couldn’t afford a hotel and speaking to whomever would listen. On June 15, 1940, he gave a speech in the city of Sedalia that would make history.

At that time, many Missourians sympathized with its slave-state history. Quantrill’s Raiders were still feted as heroes. The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan still thrived. Harry Truman had been raised there, in a family steeped in the hatreds of the post-Civil-War South, and whose slave-owning grandparents had been held in a Union concentration camp—a transgression for which the North and Abraham Lincoln could never be forgiven.

Nonetheless, before an all-white crowd of several thousand rural Missourians, some of whom would proudly admit to being active Klansmen if asked, he spoke:

“I believe in the brotherhood of man, not merely the brotherhood of white men but the brotherhood of all men before law.

“I believe in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. In giving Negroes the rights which are theirs we are only acting in accord with our own ideals of a true democracy.”

“I never did give anybody hell,” he would later demur. “I just told the truth and they thought it was hell.”

Truman’s use of the word “negro” would have caused considerable discomfort for some. It was a neutral word in those days and, in the context of Truman’s speech, it was used with respect. But it was not the respect some in his audience were accustomed to showing, and not the word some were accustomed to using. Truman himself, in casual conversation, sometimes used the harsher words of the radical South in which he was raised. But he truly believed that public office was a trust that, regardless of any personal bias, carried with it an obligation to fairly and equally represent all citizens. He soldiered on:

“If any class or race can be permanently set apart from, or pushed down below the rest in political and civil rights, so may any other class or race when it shall incur the displeasure of its more powerful associates, and we may say farewell to the principles on which we count our safety….

“In the years past, lynching and mob violence, lack of schools, and countless other unfair conditions hastened the progress of the Negro from the country to the city. In these centers the Negroes never had much chance in regard to work or anything else. By and large they went to work mainly as unskilled laborers and domestic servants.

“They have been forced to live in segregated slums, neglected by the authorities. Negroes have been preyed upon by all types of exploiters from the installment salesmen of clothing, pianos, and furniture to the vendors of vice.

“The majority of our Negro people find cold comfort in shanties and tenements. Surely, as freemen, they are entitled to something better than this…. It is our duty to see that Negroes in our locality have increased opportunity to exercise their privilege as freemen.…”

This speech became known as the “Brotherhood of Man” speech, and it was classic “give ’em hell, Harry.” It was also a seminal moment for the civil rights era in America.

“I never did give anybody hell,” he would later demur. “I just told the truth and they thought it was hell.”

To everyone’s surprise, he won one of the closest senatorial elections in Missouri history. From there his straight-from-the-hip style, his integrity, and his refusal to bow to political expediency caught the eye of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who in 1944 made Truman his running mate. On January 20, 1945, Roosevelt was sworn in for his fourth term. Eighty-two days later he died, and Harry S. Truman became the 33rd President of the United States.

“Today we stand on the threshold of a new world. We must do our part in making this world what it should be.”

During his two terms as president, Truman continued his campaign for civil rights, expanding beyond the borders of the United States and beyond the issue of race. On September 1, 1945, he spoke to the post-World War II American public:

“Today we stand on the threshold of a new world. We must do our part in making this world what it should be—a world in which the bigotries of race and class and creed shall not be permitted to warp the souls of men….”

But many in the country were less interested in the souls of men than in their bank accounts, and post-war labor strife threatened to unseat Truman. In the 1946 midterm elections, the Democratic Party was crushed, losing control of both House and Senate. Truman’s approval rating sank to 32 percent. But he persisted.

Immediately after the elections, Truman established a federal Committee on Civil Rights. One of its first recommendations was a federal law to protect the voting rights of Southern blacks and to provide federal protection against lynching. The legislation was defeated by Southern Democrats acting en bloc.

Truman refused to be stopped. On June 29, 1947, he gave another speech, this time from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Speaking to the assembled representatives of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, he addressed the need for federal civil rights protections for all:

“We must make the Federal Government a friendly, vigilant defender of the rights and equalities of all Americans. And again I mean all Americans….

“Many of our people still suffer the indignity of insult, the narrowing fear of intimidation, and, I regret to say, the threat of physical injury and mob violence. Prejudice and intolerance in which these evils are rooted still exist. The conscience of our Nation, and the legal machinery which enforces it, have not yet secured to each citizen full freedom from fear.

“We cannot wait another decade or another generation to remedy these evils. We must work, as never before, to cure them now. The aftermath of war and the desire to keep faith with our Nation’s historic principles make the need a pressing one….

“For these compelling reasons, we can no longer afford the luxury of a leisurely attack upon prejudice and discrimination.”

And leisurely he was not.

On February 2, 1948, he delivered a special message to Congress. That message was the first by a sitting president to address the question of civil rights for African Americans.

“These are the basic civil rights which are the source and the support of our democracy.”

“In the State of the Union Message on January 7, 1948, I spoke of five great goals toward which we should strive in our constant effort to strengthen our democracy and improve the welfare of our people. The first of these is to secure fully our essential human rights. I am now presenting to the Congress my recommendations for legislation to carry us forward toward that goal.…

“Throughout our history men and women of all colors and creeds, of all races and religions, have come to this country to escape tyranny and discrimination. Millions strong, they have helped build this democratic Nation and have constantly reinforced our devotion to the great ideals of liberty and equality. With those who preceded them, they have helped to fashion and strengthen our American faith—a faith that can be simply stated:

“We believe that all men are created equal and that they have the right to equal justice under law.

“We believe that all men have the right to freedom of thought and of expression and the right to worship as they please.

“We believe that all men are entitled to equal opportunities for jobs, for homes, for good health and for education.

“We believe that all men should have a voice in their government and that government should protect, not usurp, the rights of the people.

“These are the basic civil rights which are the source and the support of our democracy.”

Truman went on to ask for Congressional support in establishing a permanent Commission on Civil Rights, a Joint Congressional Committee on Civil Rights, and a Civil Rights Division in the Department of Justice; a Fair Employment Practice Commission; and a strengthening of civil rights statutes nationwide. Lastly, he addressed claims of reparation by Japanese Americans who had been sent to concentration camps (Truman’s words) during the war.

Then, on June 26, 1948, he issued Executive Order 9981, abolishing discrimination in the Armed Services based on race, color, religion or national origin. It was one of the most monumental Executive Orders in American history.

By the end of the year, Truman was up for reelection, this time on his own merits. He was given little chance. Nonetheless, he insisted that the Democratic Party platform include support for civil rights and fair employment practices. In response, a bloc of Southern Democrats abandoned the party, placed their own candidate, Henry Wallace, on the ballot and campaigned against Truman. Not one to back down, Truman used that election to become the first presidential candidate to campaign in Harlem, and the first presidential candidate to hold an integrated rally in Texas.

“…The people who are hysterical are afraid of something or other, and somebody’s got to lead them out of it.”

It was another election where everybody knew Truman would lose. The Chicago Daily Tribune prematurely printed and distributed tens of thousands of papers with the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman.” They were not the only paper to do so. And they, of course, were wrong. Truman would serve another four years, finally stepping down and returning to his home in Independence, Missouri, in January 1953.

Through his support of the United Nations’ human rights agenda, desegregation of education at all levels, a homeland for the Jewish people, and civil and religious freedom for all, Truman pushed a reluctant nation forward. In return, he was loathed. His popularity rating at the end of his presidency stood at 30 percent.

As he said when arguing for respect and tolerance for Mormons in his home community, “It’s a prejudice, and it doesn’t make any sense, but it’s there. And some people in public life take advantage of those prejudices.… But what it always is, the people who are hysterical are afraid of something or other, and somebody’s got to lead them out of it.”