-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Supreme Court Finds in Favor of High School Coach Prayer. Should Minority Religions Worry?

This February over 100 students staged a walkout at Huntington High, a West Virginia public school, protesting their enforced attendance at a Christian prayer assembly during school hours. The speaker at the assembly was an Evangelical Christian preacher who encouraged the attendees to commit to Christianity. One parent whose Jewish son was told he must attend the assembly said, “It’s a completely unfair and unacceptable situation to put a teenager in.”

A school district spokesperson has since called the incident a mistake.

Days earlier a Jewish woman reported that her daughter was advised “how to torture a Jew” during a public high school class in Tennessee. The class, which was intended to be a non-sectarian take on the Bible as historical literature, was used instead for “blatant Christian proselytizing,” according to the woman.

“[The teacher] wrote an English transliteration of the Hebrew name of God on the whiteboard. This name is traditionally not spoken out loud and is traditionally only written in the Torah. She then told her students, ‘If you want to know how to torture a Jew, make them say this out loud,’” the mother said. “My daughter felt extremely uncomfortable hearing a teacher instruct her peers on ‘how to torture a Jew’ and told me when she came home from school that she didn’t feel safe in the class.”

The school district is investigating the incident.

“We know if a Muslim teacher does what this coach did, it could spark a very different reaction.”

It is incidents like these that have made Jewish groups and representatives of other minority religions uneasy about the recent Supreme Court ruling that a high school coach was within his First Amendment rights on two points—freedom of speech and religion—to pray publicly on a publicly used, taxpayer-funded high school football field.

“We know if a Muslim teacher does what this coach did, it could spark a very different reaction, but he or she has the right to do it now,” said Edward Ahmed Mitchell, national deputy director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), which advocates on behalf of Muslim Americans.

“Will this be equally applied to all people? And will students be protected [from enforcement or intimidation]? Those are the two questions,” he added.

CAIR and other religious and advocacy groups worry that the High Court’s decision creates more problems than it solves. Where, for example, is the line drawn between a completely private expression of one’s beliefs—which is protected speech—and coercive proselytization in a taxpayer-funded public place?

Would a young person who has no religious affiliation, or who belongs to a minority faith—say a Quaker or a Jehovah’s Witness or a Jew—feel compelled to participate in such an activity in order not to get on the bad side of the adults in charge? Is there a guarantee that every single adult in authority at every public school will apply the Supreme Court decision uniformly, or will some use it as a license to impose their beliefs on others?

There’s a time and place for everything.

When the question was still undecided, organizations representing 34 minority religious groups filed a friend-of-the-court brief urging the Supreme Court to find against the coach, citing earlier instances where students from minority religions felt bullied and targeted by other students because they had opted out of prayers before or after a game. The signatories to the brief included the American Jewish Committee, the National Council of Jewish Women, B’nai B’rith International, the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, Hadassah, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Hindu American Foundation, Muslims for Progressive Values, as well as Christian groups.

Major Jewish organizations have condemned the court’s decision in no uncertain terms. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) issued a statement: “The Court’s see-no-evil approach to the coach’s prayer will encourage those who seek to proselytize within the public schools to do so with the Court’s blessing.”

The National Council of Jewish Women tweeted: “The Court is dismantling the wall between religion and state, and the impact on people—especially children, who practice a minority religion or no religion—cannot be overstated.”

Similarly, the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism tweeted: “As Reform Jews, we believe no student should feel forced to engage in religious activity at public school or choose between religious freedom and being part of a team.”

The Orthodox Jewish community was split on the matter. While The Orthodox Union, the representative organ for Modern Orthodox groups and synagogues, declined to comment on the High Court’s decision, individual groups weighed in. Rabbi Levi Shemtov of the American Friends of Lubavitch (also known as Chabad), said that for years his group has advocated for moments of silence, rather than a vocal prayer in public schools, adding, “A parochial prayer can present some real problems while a moment of silence is all but unassailable.” A moment of silence, Rabbi Shemtov argued, “gives each individual the right to worship in the privacy of their own mind even in the presence of others.”

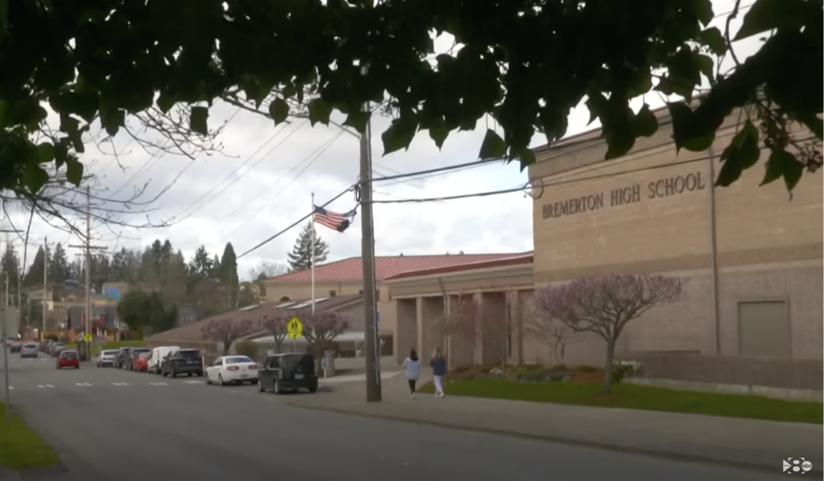

Though the Supreme Court may have banged the gavel and closed the book on the case of Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the court of public opinion has not.

The Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty, favoring the decision, had previously filed a brief of its own, contending that “for many Orthodox Jews, brief quiet prayer is a fact of everyday life, and may often have to be uttered in front of other people. If this Court were to determine that the Establishment Clause compels public schools to prohibit employees from engaging in such conduct, it could effectively bar Orthodox Jews from teaching in public schools.”

Another Orthodox group, Agudath Israel of America, favored the part of the ruling that did away with an old standard for determining whether a government action advances or blocks religion—one which Orthodox groups felt was too limiting. But the group did not favor the clause allowing public prayer in a taxpayer-funded activity. Abba Cohen, Agudath Israel’s Washington director said, “Agudath Israel has long expressed concern about and opposition to denominational public prayer and the proselytization in schools.”

All of these reactions and statements and many more which will doubtless surface in the coming weeks and months signify that, though the Supreme Court may have banged the gavel and closed the book on the case of Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the court of public opinion has not. Far from it.

The West Virginia mother whose Jewish son was compelled to attend a Christian prayer assembly succinctly summed up the problem: “I’m not knocking their faith but there’s a time and place for everything—and in public schools during the school day is not the time and place.”