-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

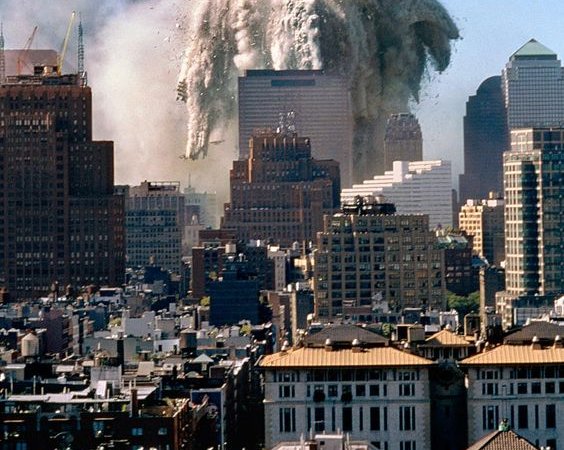

How 9/11 Brought Religions Together as the World Fell Apart

2,996 innocents died 20 years ago on September 11, 2001.

Number 2,997 died four days later. Balbir Singh Sodhi, a Sikh man planting flowers outside his gas station in Mesa, Arizona, was gunned down for his turban and beard by a self-described “patriot” in a drive-by shooting. Though it happened 2,500 miles from Ground Zero, Balbir Singh Sodhi was no less a victim of what happened at the Twin Towers than the nearly 3,000 who had perished less than a week earlier.

Since that time, nearly 140,000 other individuals have been the targets of hate crime in the United States. 140,000. Many losing their lives, many others their livelihoods, their family members, and whatever hope and color their existence possessed prior to the crime—all of them, in a very real sense, victims of 9/11.

140,000 might be better understood with an analogy. It’s the same as if every man, woman and child in Waco, Texas were the victim of a hate crime today; or every living soul in Paterson, New Jersey or Clearwater, Florida or Bridgeport, Connecticut. 140,000 is more than twice the populations of Juneau and Fairbanks, Alaska combined, a third again the population of Miami Beach and just under that of Fort Lauderdale.

Balbir Singh Sodhi was no less a victim of what happened at the Twin Towers than the nearly 3,000 who had perished less than a week earlier.

Several days after 9/11, I participated in a televised dialogue with representatives of other faiths. Those speaking were a Christian pastor, a Jewish rabbi, a Muslim youth leader and me, a Scientology minister. A lot of airtime was given to handling calls from concerned and frightened viewers needing comfort and reassurance, and the rest of the time was devoted to each of us talking about his or her faith and how recent events had impacted us. At various times we spontaneously took the other’s hand in friendship or sympathy. And we departed as friends and allies.

Around the country and around the world similar scenes played out.

On 9/11, Imam Naeem Baig, general secretary of the Islamic Circle of North America, found himself under pressure from worried Muslims to shut down his office in Queens, New York, for fear of reprisals. He ultimately decided to remain and handle the phones, while leaving the prayer area open for anyone who needed to use it.

“And then I received a call from the local Catholic archdiocese,” Baig recalled. “He said, ‘If you need anything, we are here for you.’ It was a great gesture.”

One outcome of 9/11, a candle of hope, is the widening of the meaning of “interfaith,” which prior to that tragedy referred too often to friendship and cooperation amongst the “Big Three”: Protestant, Catholic, Jewish. But in the wake of 9/11, that concept became obsolete. As one rabbi put it: “Today in the United States, you cannot have serious interreligious relations without including Islamic communities. You cannot do that without a broad base, a whole panoply of people of all religions represented in America.”

Increasing awareness that we’re all in this together has broadened the tent of dialogue to include not just Islam but other minority religions.

Author and activist Valarie Kaur is a Sikh whose family had been close to Balbir Singh Sodhi, the first innocent death post-9/11. As a Sikh, he had a beard and wore a turban as a sign of his faith, which marked him, to the ignorant, as Muslim, though Sikhism shares neither location nor the tenets of Islam, having its birth in India—not Mecca—in the 15th century, not the 7th.

Kaur commented on the fear throughout her community that they would be targeted as Muslims. “At the very, very beginning there were bumper stickers that some members of our community printed that said, ‘We Are Sikhs—Not Muslims.’ But very quickly our community realized that it didn’t actually matter to the person who was aiming the gun at us whether we were Sikh or Muslim. We fit the image of the perpetual foreigner, of the automatically suspect potential terrorist. It didn’t matter to them what we called ourselves. The violence would explode anyway.”

Increasing awareness that we’re all in this together has broadened the tent of dialogue.

In the end it was “reaching back to the love ethic at the heart of our faith” that restored a spiritual equilibrium to the Sikh community, Kaur said. “We have stood up for other religious minorities in India for centuries so why should we throw another community under the bus?”

Too often our fear masquerades as “patriotism,” and our suspicion of those who don’t look like us expresses itself in repressive acts masquerading as “security.”

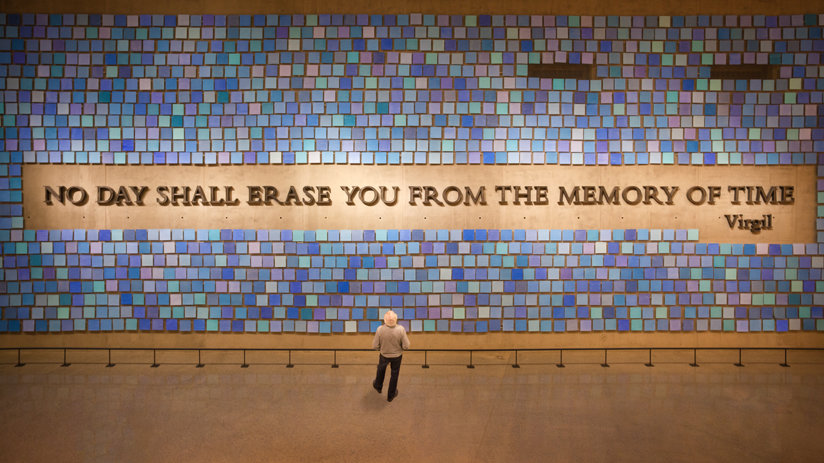

Reprisal, recrimination, repression. These actions have not stanched the wounds of 9/11, nor have suspicion, hate and fear. These are all things of darkness, inhuman and inhumane, and as things of darkness they cannot bring the light of truth and understanding the way that simple communication between good people of diverse backgrounds and faiths can.

As Kaur observes, regarding the darkness we are experiencing in our time: “Is this the darkness of the tomb, or the darkness of the womb?”

The difference is that a tomb is an ending of life and hope, whereas the womb, presages a new birth, albeit accompanied by the wrenching pain of labor.

The choice is ours which one it is.