-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

What I Tell My Friends When Scientology Is Libeled

My mother died when I was 26. At her funeral, she looked like a second-rate wax museum replica. She was all there, but she wasn’t. Something enormous was missing. I hardly recognized her.

Her personality was missing.

“Science” (those quotes are the literary equivalent of a sarcastic smirk) would have us believe that death is simply the stoppage of a complex concatenation of biochemical reactions. Really? You’re going to try to explain personality—honor, integrity, knavery, brilliance, creativity, cowardice, insight, persistence, greatness, and the whole panoply of human phenomena—as mere biochemical reactions in meat? I don’t believe it.

And what of free will? Chemicals do not act. Chemicals re-act. Free will acts. Free will requires that something sit in the driver’s seat. Is there some heretofore undiscovered “free will” gland which is puckishly playing havoc behind the scenes? I don’t believe it.

So what do I believe?

That the spark of life, Bergson’s “élan vital,” is the footprint of the spirit.

Certainly the body and mind are component parts of life. But they are subordinate. Man is a spirit, inhabiting a body and using a mind. This is old news, by the way. It is roughly what man has believed ever since he crawled up on the shore and blinked at the sun. It is a symptom of our modern conceit that we have forgotten.

Don’t buy it? Are you capable of free will? You know you are. Who or what is in the driver’s seat? Ponder that and you ponder eternity.

What does Scientology displace? The notion that man is a victim, that hormones control, and that death is the final curtain.

This is all too obvious. So why is virtually nothing known about this spirit? We have Newton’s three laws of motion, the theory of relativity, and other theorems and laws too numerous to mention to help us understand the physical universe. Where is the equivalent study on the spiritual side?

That is Scientology. And using Scientology, the spirit can rediscover and rehabilitate itself.

What does Scientology displace? The notion that man is a victim, that hormones control, and that death is the final curtain.

People will scoff. “Where’s the science?” they will ask. Such people’s addiction to authority’s approval is far deeper than any heroin addict’s to his drug. Science is walking along the seashore, peering at and cataloging every grain of sand. There is value in that. But philosophy is looking up from the beach to try to find the sun. A man focused on the sand is bewildered by shadows; there is no sun. Scientology is applied philosophy.

Man is a spirit. That spirit impinges on the physical universe to generate life. It’s that simple.

The bludgeoners who would attempt to address life through psychosurgery, electric shock and drugs are simply performing the modern-day equivalent of trepanning, bloodletting and leeches. In the mental and spiritual realm, we are still in a barbarism, and future generations will see it so.

Scientology is a quantum leap out of that barbarism. As such, it cannot help but stir opposition.

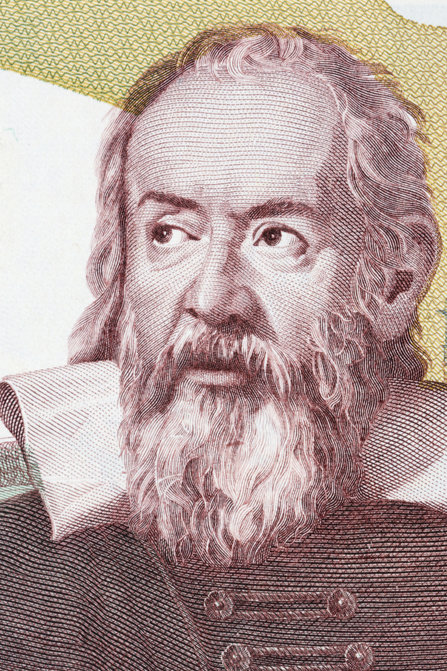

In 1633, Galileo was tried and found guilty of heresy and confined to house arrest for the remainder of his life for correctly observing that the earth revolved around the sun and not vice versa. In that same century, William Harvey correctly observed the manner in which blood circulated through the body. His findings ran counter to 1,400 years of “science” which had come to rely on the incorrect observations of Galen. “I would rather err with Galen than be right with Harvey” was the battle cry of his contemporaries, and they drove him into seclusion.

No, man does not accept new ideas gracefully. It is actually astonishing that Scientology has been met with as much acceptance as it has. But opposition is inevitable. It is the mark of progress.

I am proud to be part of that progress. And I think my mother would have been proud of me.