-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

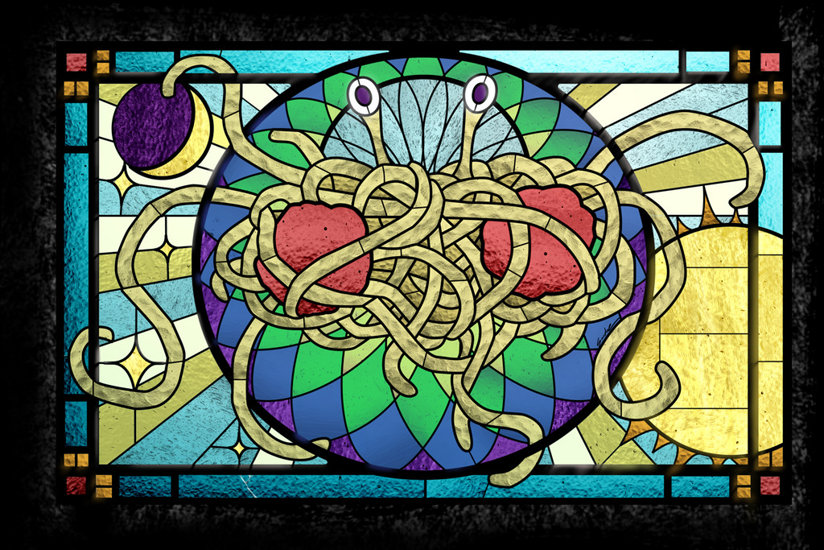

The “Church” of the Flying Spaghetti Monster and its Debt to the Quakers

Imagine yourself at your local DMV office renewing your driver’s license. You’ve spent several hours filling out forms, standing in various lines, demonstrating your knowledge of the rules of the road and having your vision tested. You’ve made it to the last part of the process—taking your photo for your new license. Much to your surprise the person standing in front of you has a colander on top of his head. You blink a couple of times but it’s still there. The pasta strainer is not a figment of your imagination. The person with the unusual headgear is probably a member of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, aka a Pastafarian.

As you can guess, the Pastafarians are not members of a real church. Based on a parody created by a college physics student in 2006 to protest teaching the possibility of intervention by God as a reason for evolution, the “church” grew into a loosely organized mockery of religious faith and practices. In addition to the colanders, its members show their contempt for real religious beliefs when they demand to take Fridays off (a “religious holiday”) and to wear pirate garb to work. Government agencies in certain countries have approved their claims.

What the Pastafarians are ridiculing is the practice of allowing people with sincerely held religious beliefs to be exempted from rules or norms usually imposed on members of society but which violate their religious beliefs. A religious holiday on a normal workday is the most common example. Another example is that of Orthodox Jews, Sikh men and Muslim women being allowed to wear head coverings even when in violation of normal dress codes. Many countries have laws which safeguard such practices. These protections are usually referred to legally as “religious accommodation.”

People who are willing to take a stand for their principles are very valuable to a society and by protecting them and allowing them to uphold their own standards, we all benefit.

The Pastafarians’ demand for odd “accomodations” is an attempt on their part to show their scorn for religion generally. Well, okay. Engaging in satire is a right that members of a free society enjoy. But it’s also true that people make fun of things they don’t understand. In the case of the Pastafarians, their disdain for true religious beliefs—and also what comes across as cynicism towards people with strong convictions of any kind—leaves them unable to comprehend, for example, why a male Sikh would insist on wearing a turban, or a Jewish pitcher would give up a World Series start because it conflicted with a religious holy day (as happened with the great Sandy Koufax many years ago). But if they knew their history a little better, the Pastafarians would see that the struggle of religionists to win accommodations—and the eventual willingness of governments in more enlightened countries to grant them such protections—has helped nonbelievers as much as it has Sikhs, Muslims, Jews and others.

I’m referring specifically to the Quakers and their long battle to win the right not to have to swear oaths. When the Quaker movement began in 17th-century England, it was mandatory to swear an oath on a Bible to be allowed to testify or defend one’s rights in court or assume a post in government. But the Quakers believe the Bible dictates that one should not “swear” to things but simply speak the truth. Thus, when called before a court, Quakers refused to take oaths. For this, and other strong-willed stands, they faced heavy persecution.

For example, a 1662 law called for fines, seizure of property, imprisonment and finally expulsion from England for any Quaker who refused to take an oath when required. These penalties were frequently imposed by a very intolerant English government. However, the Quakers fought back as they always did by simply refusing to comply with laws they believed unjust. By the end of the 1600s, they had worn out their oppressors and English law changed. Quakers faced similar mistreatment in the American colonies (except in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, colonies they founded or helped found) but ultimately prevailed on this side of the Atlantic as well. Laws in the colonies eventually permitted affirmations in addition to oaths, i.e. instead of swearing to God, it became permissible to simply affirm that one would tell the truth, which remains the law to this day. And when the U.S. Constitution was drafted in 1787, it allowed incoming Presidents and other federal officials to either swear or affirm to uphold the Constitution of the United States. So, thanks to the Quakers, the right to hold office and to appear in court is open to believers and nonbelievers alike, and the Pastafarians aren’t required to swear to God in order to defend their legal rights, which I imagine they appreciate. The Quakers also created a precedent for other religious (or atheist) accommodation. In fact, ironically, it is because of the courage and persistence of this religious group that the Pastafarians’ parody has achieved at least some governmental acceptance.

Anyone with strong beliefs, religious or otherwise, can identify with the Quakers. I’m personally very grateful to them—the strength they showed in the face of adversity made it possible for other religions, including Scientology, to be practiced freely in later years. People who are willing to take a stand for their principles are very valuable to a society and by protecting them and allowing them to uphold their own standards, we all benefit. The Pastafarians—who are safeguarded by a legal system which permits the right to be different—besmirch themselves when they attack the very people whose willingness to give of themselves afforded the Pastafarians the freedom to malign others.

I’ll close with a word of advice to the members of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster: your right to scorn religious beliefs and practices is protected, but consider the people who fought to give you that right and you might choose to treat them with a little less disdain.