Charlie Hebdo: Freedom of Expression and Its Responsibilities

On a January morning in 2015, two gunmen forced their way into the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and, in a fusillade of bullets, murdered the editor as well as 11 others. Still others were wounded but survived. The attackers were radical Muslims whose stated goal was revenge against the magazine for publishing cartoons of the prophet Muhammad nine years earlier, an act that most Muslims regard as sacrilege.

Over five years later, the Charlie Hebdo murders are again in the news as 14 accomplices of the two killers are now on trial in a Paris courtroom for their role in the killings and four related slayings in a kosher supermarket several days later. The two Charlie Hebdo assassins and the supermarket killer died at the hands of the French police at the time of the two attacks.

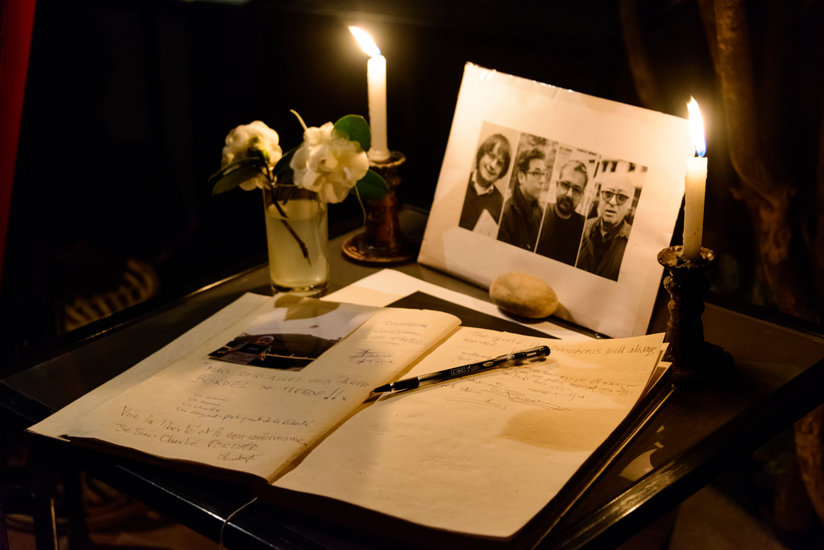

When the murders took place in 2015, it spurred an outpouring of sympathy and support for Charlie Hebdo as well as condemnation of the assassins with “Je Suis Charlie” (“I Am Charlie”) signs appearing around the globe as well as public marches and rallies, the largest of which, in Paris, attracted well over a million people.

Those who attended the demonstrations and held up the “Je Suis Charlie” signs were standing up for more than one magazine. Most people understand that a free press and free expression are essential to a democratic society that upholds the rights of the people and that the Charlie Hebdo killers were striking at one of the most basic pillars of a free society. “This is serious, this was an attack on freedom, we cannot allow this,” said one marcher adding that “our values are liberty, equality and fraternity and we cannot allow terrorists to dictate to us.” Some demonstrators held up pencils.

Muslims, however they may have felt about the cartoons, joined the demonstrations, including the King of Jordan who appeared with other heads of state in Paris and a group of Muslims in Madrid displaying signs that said “not in our name.”

Charlie Hebdo has continued to publish. Its current staff work in a confidential location and maintain tight security. The newspaper commemorated the start of the trials by republishing the original cartoons with the headline “Tout Ça Pour Ça?” (“All That For This?”). According to the current editor, “To reproduce these cartoons in the week the trial... opens seemed essential to us.” The head of the French Counsel on Muslim Worship advised his co-religionists to ignore the cartoons and condemned violence, stating that the right to caricature is protected as well as the right to like or dislike it.

A society that values and upholds freedom of expression and religion cannot make blasphemy a crime.

It is absolutely necessary that all who participated in the killings be brought to justice. The horrific violence perpetrated against a roomful of people for publishing something the killers found objectionable is a threat to any society that wishes to encourage freedom of expression and of course also freedom of religion. Had the murderers and their accomplices stopped and thought about it for a minute, the same concept of a free society which allows magazines such as Charlie Hebdo to exist also enables Muslims to practice their religion as a minority openly in France and other Western countries.

Commenting on the republishing of the articles, President Emmanuel Macron stated, “There is in France a freedom to blaspheme which is attached to the freedom of conscience.”

I agree with President Macron that a society that values and upholds freedom of expression and religion cannot make blasphemy a crime. I also feel compassion for the Charlie Hebdo victims and further believe the refusal of the current staff to be intimidated should be acknowledged and respected. However, Charlie Hebdo’s publishing of cartoons that members of a faith regard as blasphemous and offensive needs to be viewed not from the perspective of whether it should be illegal or whether it should be met with violence, but from the perspective of an honest inquiry: what ethical restraint should a media outlet exercise on itself and what should be the public response when it violates its responsibilities to society?

One of the four guiding ethical principles of journalism according to the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics is “Minimize Harm. Ethical journalism treats sources, subjects, colleagues and members of the public as human beings deserving of respect.”

Did Charlie Hebdo follow that precept by publishing the cartoons?

Satirists, as do all members of the media, have a responsibility to minimize the harm that could be brought about in the process of their reporting.

There is a question, of course, as to whether satire should be judged by the same standards as regular journalism. After all, no one in the United States who reads The Onion thinks they are looking at regular news. But that is splitting hairs, since satire has as much potential to create harm as straight reporting.

Satire is valuable to a society. In addition to the humor it provides, it can often point out the illogic of a situation more clearly than matter-of-fact reporting. But it has the capacity to wound and those who engage in it need to evaluate whether the social value of what they are doing is greater than the harm. Is there some social value in denigrating the beliefs of a billion plus people about God? I can’t see it any more than I can see value in insulting people because of the color of their skin, their height or their weight.

Furthermore, as critics of Charlie Hebdo have pointed out, the Muhammad cartoons are not the only time that the magazine has gone beyond the bounds of a decent regard for others. To cite one of many readily available examples, in 2016 a Charlie Hebdo cartoon portrayed the victims of an earthquake in a small Italian town as types of pasta.

(Photo by Jose Carlos Alexandre/Shutterstock.com)

Satirists, as do all members of the media, have a responsibility to minimize the harm that could be brought about in the process of their reporting. However, as the above examples illustrate, sometimes they don’t. What should the rest of us do when cartoonists and writers get too enamored of their dexterity with their pencils and forget that their words and pictures negatively affect the lives of real people? The same question also applies to ordinary journalism when it oversteps the bounds of honest, straight reporting and is used to malign or to pursue vendettas or hidden agendas.

While there is no rote answer to that question, I believe that upholding free expression has two sides. One side, of course, is keeping it free. The other, perhaps not as obvious, is insisting that expression contribute positively to society or at least not weaken the social bonds that make freedom possible. There’s obviously subjectivity about what is good and bad and it would be all too easy to resort to censorship in the name of protecting the public welfare, but there is no reason to stand by and watch people be denigrated for their religion, race or anything else in the name of freedom of the press. In the case of the Muhammad cartoons, many Muslim sources have explained calmly why the cartoons are an affront to their beliefs. They may not have been as widely publicized as the murderers, but they quietly helped create dialogue and understanding.

All of us should learn to recognize journalism that breaches its responsibility to treat its subjects with respect and seek to persuade its creators to develop the ability to see things from a broader viewpoint. Groups and individuals that have been maligned have a responsibility, not just a right, to present their own story and undercut the false or negative impressions put out by those who would intentionally make less of them.