-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Supreme Court to Decide Whether State Prisoners Can Sue Over Religious Freedom Abuses

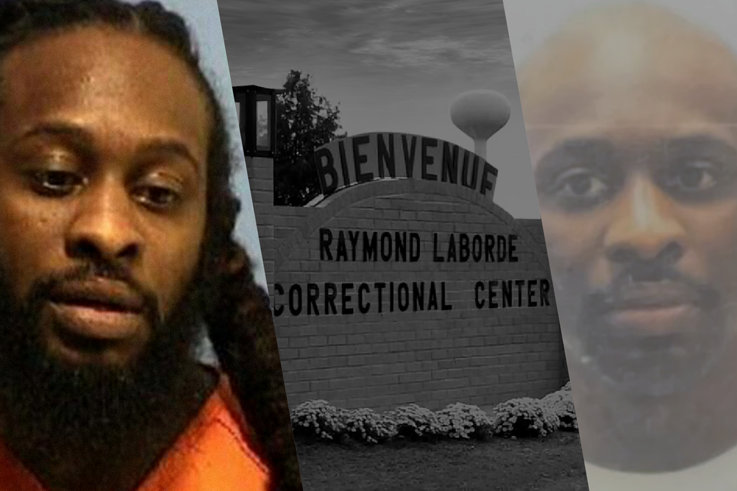

The Supreme Court has now heard arguments in the case of a Rastafarian who claims his religious rights were violated by a Louisiana state prison. STAND has been tracking Damon Landor’s case since it first emerged, following his appeals through the lower courts.

Landor was convicted of drug possession and incarcerated at Louisiana’s Raymond Laborde Correctional Center in 2020. In keeping with his faith, he had grown his hair almost down to his knees over the course of nearly two decades, his dreadlocks reflecting a central tenet of Rastafarianism: that long hair is a physical manifestation of devotion, and a spiritual bond with the earth and the universe.

“We are trying to ensure that people held in state prisons can get the same protection for their religious exercise.”

When prison officials ordered his hair cut, Landor objected, handing a guard a Louisiana court decision stating that federal religious freedom law bars the state’s prisons from forcing Rastafarians to cut their hair. The guard threw the document in the trash, handcuffed Landor to a chair, and cut his hair while two other guards held him down.

Landor is now seeking damages from the officials and prison staff responsible, but a federal judge and an appeals court have already ruled against him—finding that the law doesn’t allow state prison inmates to sue officials for damages.

To be clear, no one disputes that Landor’s rights were violated or that he was subjected to abuse. Even the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections “condemns” what happened to him in “the strongest possible terms.”

But the sticking point for the courts has less to do with faith and more with the exact language of the law and legal precedents: Under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), several federal appeals courts have barred plaintiffs from seeking monetary damages against officials in their individual capacity. By contrast, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) allows suing federal officials, including in prisons, for damages, but not state officials.

Given that Damon Landor was a state prison inmate, he has no clear case.

“If Damon had been held in a federal prison, he would have been able to sue the officer for damages. We are trying to ensure that people held in state prisons can get the same protection for their religious exercise,” Zack Tripp, Landor’s attorney, said.

Adding to the challenge is a 2011 Supreme Court ruling limiting whom inmates may sue—according to that decision, Landor can seek damages only from individual prison employees, not from the state of Louisiana.

As it stands, the court may be leaning toward the wording rather than the spirit of the law. Several justices, for example, appeared focused on whether prison employees were properly on notice that they could be personally liable. Justice Gorsuch, for instance, asked whether the prison officials had ever agreed—by contract, consent or any other binding commitment—to be subject to lawsuits or personal liability. It’s a question that often arises when individuals, rather than institutions, are named as defendants.

Arguing before the high court, Tripp said that granting Landor’s claim is essential to protecting prisoners’ rights. If defendants can’t collect damages, he said, prison officials “can treat the law like garbage.” He called Landor’s case “the poster child for RLUIPA violation.”

In recent years, the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled in favor of the plaintiff in several high-profile religious freedom cases, including religious parents objecting to school materials that conflicted with their faith, a football coach seeking to pray on a public school field and a web designer unwilling to work with couples whose lifestyle clashed with her beliefs.

Damon Landor’s case stands apart in two key respects. First, there is no dispute that his religious freedom was seriously violated (it was). Second, the court must choose whether to adhere strictly to the statute’s wording or interpret the law in light of its broader purpose.

In the end, Landor’s case, which has inspired amicus briefs by 35 religious organizations representing a wide spectrum of the faith community, will succeed only if the court honors the law’s intent.

Or as Earl Warren, a Supreme Court chief justice, once wrote, “It is the spirit, not the form of law that keeps justice alive.”